| ||||

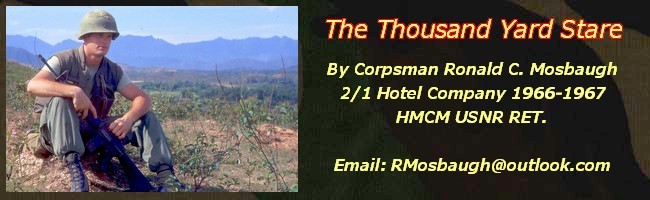

The Thousand Yard Stare

Even though I left Vietnam fifty years ago, subconsciously I am still there. The trauma I experienced and witnessed is always with me. I can still smell the burned bodies, the blood of casualties, the Vietnamese people, and the pungent odor of explosives. I can still hear the voices of dying soldiers and the cries of those who just lost an arm or leg. Forever nineteen in this endless nightmare, I see sights that are difficult to comprehend, especially for someone so young. Our youth was stolen from us, but we had to survive. The invisible wounds of war linger, however, and they have tormented me for years.

For several months during 1997, I dealt with depression and low self-esteem. Many times my family and friends would ask me where I was mentally because I was doing the “1000-yard stare.” What they didn’t know was that my mind was back in Vietnam, and I was staring into emptiness. I separated my mind from my body. Emotionally I was numb and detached from society. It’s like I was part of a puzzle, but couldn’t find where I belonged. I even contemplated suicide. However, being a Christian and having a family, I couldn’t do that. I did pray earnestly, however, that I might have a heart attack and just go away.

I knew I needed help, but it wasn’t easy to admit. Finally, I made arrangements to check into the VA Medical Facility in Topeka, Kansas, for a seven-week, in-house program for Post- Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD). I drove from Joplin to Topeka by myself. Many times I wanted to turn around and go back home, but somehow I kept going.

I walked into the PTSD facility, and the first thing the psychologist told me to do was: “Write down your entire trauma.” What a ridiculous request! I told him I didn’t talk about that to my family or anyone else for that matter. This was my private world, and I didn’t want to think about it. It was my private black box if you will. The psychologist then responded, “If you don’t write down your trauma, you might as well turn around and go back home. We can’t help you.”

Wow, that jolted me. I realized I had to give this some serious thought. I couldn’t go back home because I knew I had some serious mental issues, and I was on the edge of disaster. I finally gave in, but I told the psychologist, “I can’t write down my entire trauma. I was in Vietnam for thirteen months, and I ran hundreds of patrols.” I told him that I dealt with multiple trauma episodes, and many of my experiences overlapped one another. There was too much trauma blended together, and it was difficult to separate out the episodes.

War trauma is much different than a one-event trauma, such as a rape, car wreck, robbery, tornado, or whatever. I know people get PTSD from some of these occurrences, but it does not compare to what warriors experience in war. In my way of thinking, war is the worst kind of trauma. The psychologist agreed with me, but he said to do the best I could.

This had to be handwritten. My hands were shaking so much I could barely read what I was writing. I sat there for the longest time contemplating how I was going to write this story. Twice I had to go to the bathroom. I suppose I was stalling more than anything. This line of thinking was alien to me and looking back was very hard for me to process. It was a road I did not want to travel. The road was dark, winding, and narrow. I kept seeing a sign that said “Danger ahead. No Trespassing.” I did not want to open my Vietnam Pandora’s box. To do so would release the demons.

The psychologist watched me at times. I’m sure he knew I was in deep thought. I believe his name was Terry Falk. He was a soft-spoken man who talked in a monotone voice. At times he was hard to hear. Finally, he said, “What is the first event you think about when someone mentions Vietnam?”

My first thoughts were of a Vietcong looking at me from twenty feet away. I was treating a wounded marine. The Vietcong could have killed me instantly, but he chose not to shoot. Many nights I have suffered nightmares from this event.

This was also the same patrol on which we walked into an ambush and were overrun by the Vietcong and North Vietnamese army. This time, many of the marines were in actual hand-to-hand combat. Out of ninety marines, only twenty-six of us walked out.

Once I got my thoughts together, I picked up the pen and started writing. I don’t mind telling you, the tears flowed. After a few paragraphs, other thoughts and memories occurred to me. Things I had not thought about for years. Even today, I still have events come to mind that I haven’t thought about in many years.

In the days that followed that first check-in, these fresh and intrusive memories brought on nightmares and flashbacks. The pharmacist increased my medication to compensate for the demons in my head. This was not unusual. On occasion, a new patient would arrive who would suffer withdrawal symptoms because of the drugs he had been on before. They would send him to another ward to help him readjust.

I attended a group trauma and psychotherapy class with Barbara Book, a psychologist we respected immensely. I also spoke individually with another psychologist about my trauma. I learned that many of the other war veterans experienced some of the same emotions and trauma I did. Before coming to Topeka, it was all about me, but I was starting to see a bigger picture.

The first week at the facility, I was in lockdown. In other words I could not leave the building for the first week. Generally, I started class work at 7:30 a.m. and quit at 5:00 p.m. Many days I had a lesson to complete before the next day. I could walk next door to the cafeteria to eat meals, but I had to have another patient with me. After that first week, I could leave the building after classes and even receive visitors.

In time, I started to understand what I was going through. I could get my thoughts together now and reason out why the demons possessed me. It was really weird but there was something about writing things down that brought relief. Looking at a traumatic event on paper and processing it became a healing mechanism. I could now separate the events into categories and get a better handle on them. When I had something to work with, the healing began. I could create an order to my thinking and visualize the actual events.

During our program on Wednesday evenings, we traveled to a farmhouse at the edge of town. An organization called “Point Man International Ministries” was created to help veterans who suffer from PTSD. The leader was a veteran helicopter pilot who flew in Vietnam. His family and several volunteers helped in making us feel at home. They always served an outstanding meal that was much appreciated. Point Man taught us to be better disciples and to live a Christian life. They stressed that the only way to combat PTSD is through God’s help.

At the end of my seven-week, in-house therapy, I didn’t want to go home. I was protected from the outside world, and all my needs were met. This was a common response from most of our graduates. We had finally started to recover from the hell we had lived in for over forty years, but at least now we had several tools to use in combating our trauma.

Creative writing has helped me to deal with PTSD. Don’t get me wrong, I will always have PTSD, but now I have an outlet to help me become a better person. Writing has helped me to be more aware of some of my triggers, such as a sound or sight that causes me to relive events. I deal with it at that moment. I write down my stories and concerns and look at it on paper or the computer screen. My trauma seems to come alive with the writing, but I can then process it and figure out a way to win the battle of the demons.

I have found that people enjoy my stories, and they are well received. This has helped to improve my low self-esteem and my negative attitude. It has actually changed my perspective on life. It has helped me to grow and to be a better person. Writing brings great healing to the body, mind, and soul!

I read a story on the internet not long ago that said research is just now untangling a seemingly intricate dance between post-traumatic stress and post-traumatic growth. The story is about a shattered vase. “Imagine that one day you accidentally knock a treasured vase off its perch. It smashes into tiny pieces. What do you do? Do you try to put the vase back together as it was? Or do you pick up the beautiful colored pieces and use them to make something new—such as a colorful mosaic? When adversity strikes, people often feel that at least some part of them—be it their views of the war, their sense of themselves, their relationships—has been smashed.”

So many times the warriors who try to put their lives back together exactly as they were remain fractured and vulnerable—but those who accept the breakage and build themselves anew become more resilient and open to new ways of living.

I still attend PTSD drop-in sessions in Mt Vernon, Missouri. There are fifteen to twenty Vietnam veterans who attend bi-weekly. We support one another and enjoy the camaraderie. We are all making progress in our daily lives.

I enjoy the writing of Joseph Conrad. He was a Polish-British writer regarded as one of the greatest novelists. As Conrad wrote, “My task, which I am trying to achieve, is, by the power of the written word, to make you hear, to make you feel – it is before all, to make you see.” This is my greatest desire, to help you understand the warrior and the trials we faced.

Another quote by Joseph Conrad was, “Facing it, always facing it, that’s the way to get through. Face it.” This could apply to PTSD. We need to face it, accept it and go forward.

You cannot do this on your own. We all need to ask God to help us and to guide us daily.

HMCM Ronald Mosbaugh

USNR Retired 31 years